Myths and facts about placebo and nocebo effects

Introduction

The idea that our thoughts and expectations can influence our physical health has long been the subject of debate and research. In this article, I try to examine some of the most common myths and misconceptions surrounding placebo and nocebo effects, describing scientific findings and insights from clinical practice.

What are placebo and nocebo effects and how do they differ from each other?

In order to put together an article about placebo, nocebo and their effects, modes of action and myths about placebo, it is first important to define what a placebo or nocebo is.

Placebo is derived from the Latin verb placebit what – you like it – means. Most people understand the word “placebo” as a term for fake medicine. It is often associated as a “frequently administered ineffective agent to serve as a control element during an experiment and to prove or disprove the efficacy of a real drug or other test”.

“Nocebo” is derived from the Latin nocere, which means – damage – . The most common definition of the nocebo phenomenon is: the cause of illness (or death), through the expectation of illness (or death) and the associated emotional states

(Hahn1997)

.

The legacy of the negative attitude and mindset towards the placebo effect

Unfortunately, there is still often a reductive view in thinking that the psyche functions separately from the body. “Real” Pain is therefore associated with clinical evidence of pathology and/or tissue damage (biogenic model). Pain without such evidence is considered “psychogenic” (Gamsa 1994) .

Society still often equates the placebo effect with charlatanism and regards it as a form of non-therapy. Patients who respond positively to placebo therapy are sometimes portrayed as having inadvertently revealed the falsity of their symptoms. This attitude not only interprets the patient’s pain as unreal and imaginary, but also calls into question the patient him/herself and often portrays him/her as mentally unstable or easily influenced.

However, the placebo effect is being studied more and more and is becoming increasingly important and influential in medicine and everyday clinical practice.

With this in mind, I would like to address the 3 most common misconceptions about the placebo phenomenon:

Placebo myths:

1. placebo responders are gullible

It is usually assumed that placebo responders belong to a certain neurotic group. They would be gullible, these people lack education or these people are simply overanxious.

The fact is that the percentage of placebo responders in studies can range from 0 to 100 % depending on the study design and the circumstances of the study.

Placebo analgesia (insensitivity to pain) occurs in people with “normal” personalities, different levels of education and from all social classes

(Stam & Spanos 1987)

.

2. placebo only influences mental illnesses

One hypothesis is that placebos only affect the affective (unpleasant)

component of pain, especially anxiety. One study showed that placebo reduced the fear of toothache, but did not affect the intensity of the pain (Gracely et al. 1978) .

However, there is increasing evidence that placebos also reduce the sensory components of pain as well as the physiological, functional and behavioral symptoms of disease.

There is a growing number of well-controlled, double-blind studies that

confirm significant physiological effects of placebo therapy.

For example, a comparison of different intensities of ultrasound (including zero) clearly showed that placebo ultrasound therapy produced the greatest reduction in pain, swelling and jaw tension after wisdom tooth extraction compared to active ultrasound

(Hashish et al. 1988)

. Such and other evidence refutes the myth that placebos do not affect real physiological symptoms such as tissue inflammation.

The placebo effect was not due to the effect of the tissue massage by the ultrasound probe. The strongest effects occurred when both the therapist and the patient believed that the ultrasound device was switched on. This and other important studies on ultrasound and the additional evidence of the power of patient and practitioner belief in physiological changes (Gracely 2000) should convince even the most skeptical that placebo research is important for research and clinical practice.

3. placebo effects are only short-lived

Another assumption lies in the duration and effect of a placebo. It was assumed that placebo effects were only short-lived.

This must be contrasted with the results of the study, for example:

by Cobb and colleagues, where the improvements from placebo surgery lasted for SIX months,

(Cobb et al. 1959)

. This was the first indication that the myth that placebos only have a fleeting benefit was being dispelled.

Placebos reduced the size of endoscopically measured duodenal ulcers by 10-91%, on average 46%, compared to the use of the drug cimetidine

(Moerman 1983)

.

Using strict criteria, placebo was found to objectively improve motor function in all areas of Parkinson’s disability, although bradykinesia and rigidity were favored over tremor, gait, balance, and midline function

(Goetz et al. 2000).

Both placebo and active stimulation current therapy relieve back pain in some patients for up to 12 months (Marchand et al. 1993).

Similar long-term results were achieved in the randomized clinical trial with stimulation current therapies for pain in patients with spinal metastases.

Improvements of 10 or more points in the Hamilton Depression Scale or the Beck Depression Inventory are not uncommon in depression studies (Leuchter et al. 2014; Stahl et al. 2010), so that the strong placebo effects are also held responsible for the fact that the proof of efficacy for drugs is becoming increasingly difficult, especially in the field of psychotropic drugs.

A large number of randomized studies and also meta-analytical studies (Price et al. (2008) prove the effectiveness of the analgesic placebo effect. In some cases, high effect sizes (d = 2.29) were found in studies that specifically investigated the mechanisms of action of the placebo effect.

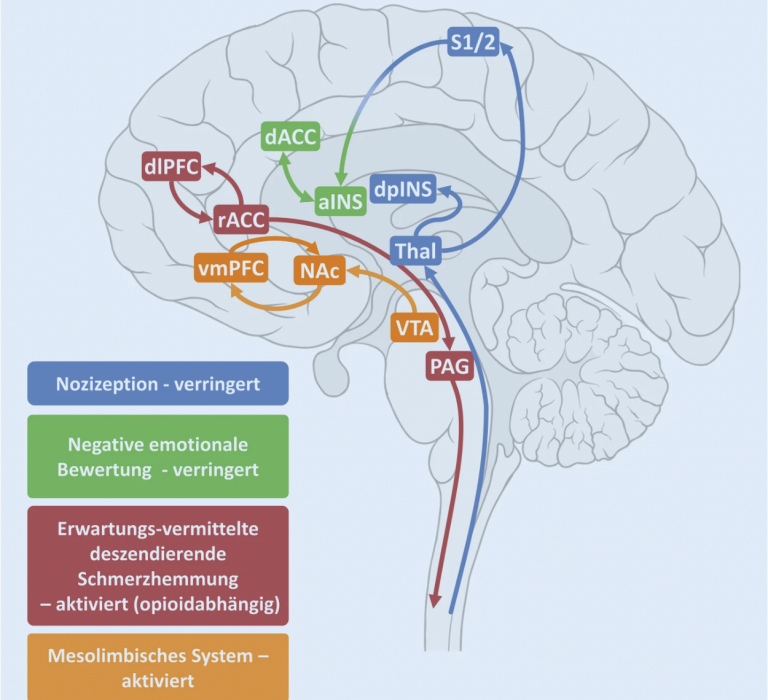

The analgesic placebo effect can therefore be classified as a clinically relevant factor (Klinger et al. 2017b).Beyond the effectiveness of the analgesic placebo effect, the studies show that there are empirical findings on psychological, neurobiological and neuroanatomical modes of action and mechanisms of the analgesic placebo effect.

What mechanisms underlie the placebo and nocebo effects and how do they affect the body?

The exact mechanisms underlying the placebo and nocebo effects are not yet fully understood. It is assumed that they are linked to the release of certain neurotransmitters in the brain. Placebo effects can stimulate the release of endorphins and other natural painkillers in the brain, while nocebo effects can increase the release of stress hormones such as cortisol.

More detailed information on the biochemical relationships can be found in this study from 2022:

Neurobiological and neurochemical mechanisms of placebo analgesia

There are also a number of processes relating to the mode of action of the placebo effect that have already been better researched and therefore also allow conclusions to be drawn about the mechanisms of action of the placebo effect:

1. processes of classical conditioning

2. expectation processes

There is clear evidence that these two psychological mechanisms of action are interactively linked (Colloca et al. 2008b; Kirsch et al. 2004; Klinger et al. 2007; Stewart-Williamsand Podd 2004).

What role do expectations, the environment and interaction with healthcare professionals play in the development of placebo and nocebo effects?

A patient’s expectations of treatment can be strongly influenced by their environment and the way they are treated. how the treatment is presented. For example Positive expectations are reinforced by trust in the treating therapist or by positive experiences with a particular treatment. On the other hand, negative expectations can be caused by a pessimistic attitude of the patient or by negative experiences in the past.

What ethical considerations need to be taken into account in connection with the use of placebos in clinical trials and patient care?

The use of placebos in clinical trials and patient care raises a number of ethical issues. Above all, it is morally justifiable to administer an “ineffective treatment” to a patient in order to take advantage of the placebo effect.

There are research results that work with “open placebo administration”, i.e. the patients knew that they were receiving a placebo.

These first clinical studies show that open administration of placebos can also be effective: The first study was conducted on patients with irritable bowel syndrome , who were randomized to a no-treatment group or a 3-week treatment with placebos (twice daily).

The patients received the following information about the placebo treatment:

1. Placebo effects are very effective,

2. The body can react automatically to the intake of placebo treatments .

3. A positive attitude towards placebos can help, but is not a prerequisite

4. Conscientious, regular intake is of great importance.

The open administration of placebos combined with the above-mentioned instruction led to a significantly greater global improvement in symptom severity after 3 weeks. The impact on the quality of life fell just short of significance. This study showed for the first time that open administration of placebos can also be effective (Kaptchuk et al. 2010).

How can patients themselves help to use positive placebo effects and minimize negative nocebo effects?

Patients cancontribute themselves use positive placebo effects and minimize negative nocebo effects by consciously creating positive expectations and beliefs. about their health and treatment , create a supportive environment and maintain open and trusting communication with their therapeutic professionals. They can also play an active role in their own recovery and adopt a positive attitude towards treatment, improving the effectiveness of the treatment and increasing their well-being.

Thoughts at the end

- Placebo also takes place when a doctor administers medication, in that we assume that this medication will help us. This means that a form of placebo is already being used here.

- Every therapist/doctor should be aware that their actions and communication can trigger a placebo or even a nocebo in patients.

- Failed treatments can provide a foundation to promote negative expectations in pain relief and contribute to learned expectations of treatment failure and thus negative biophysical responses. The repetition or persistence of this pattern contributes to the development of chronic pain.

Countless negative cognitions and beliefs are generated in patients when expectations of pain relief are frustrated.

and remain unfulfilled. (Hildebrandt et al. 1997) - Placebo treatment is not to be equated with “no treatment”.

Conclusion:

Am I questioning evidence-based practice? NO ! not at all.

In my opinion, however, it is necessary to develop an approach that includes the evidence that factors such as communication, the relationship between patient and therapist, can influence treatments and promote or impair successful treatment.

Far from being a threat to the evidence base of therapy, I believe that the placebo phenomenon offers exciting opportunities to work with and research. In the long run, the placebo phenomenon is a friend of the therapist and the patient that can and should be used with good intentions.

References and sources:

- Hahn R A 1997 the nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Preventive Medicine 26:607-611

- Gamsa, A 1994 The role of psychological factors in chronic pain II. A critical appraisal. Pain 57:17-31Stam HJ, Spanos NP 1987 Hypnotic analgesia, placebo analgesia and ischaemic pain: the effects of contextual variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 96:313-320

- Gracely RI 2000 Charisma and the art of healing, In: Devor M, Rowbotham MC Wiesenfirld-Hallin Z (eds) Proceedings of the 9th World Congress on Pain: Progress in Pain Research and Management, Vol 16.IASP Press, Seattle 1045-1068

- Cobb LA, Thomas GI, Dillard DM, Merendino KA, Bruce RA 1959 An evaluation of internal mammary artery ligation by a double-blind technique. New England Crombez Journal of Medicine 260:1115-1118

- Goetz CG, Leurgens S, Ramn R, Stebbins GT 2000 Objective changes in motor function during placebo treatment in PD. Neurology 54(3)710-714

-

- Meaning, Medicine, and the ‘Placebo Effect’ January 2002 DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511810855 Publisher: Cambridge University PressISBN: 9780521806305 Authors: Daniel E Moerman University of Michigan-Dearborn

- Is TENS purely a placebo effect? A controlled study on chronic low back pain Serge Marchand, Jacques Charest, Jinxue Li, Jean-René Chenard, Benoit Lavignolle, Louis Laurencelle Affiliations expand PMID: 8378107 DOI: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90104-W

- Role of pill-taking, expectation and therapeutic alliance in the placebo response in clinical trials for major depression Published online by Cambridge University Press: 02 January 2018 Andrew F. Leuchter, Aimee M. Hunter, Molly Tartter and Ian A. Cook

- Agomelatine in the treatment of major depressive disorder: an 8-week, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial Stephen M Stahl, Maurizio Fava, Madhukar H Trivedi, Angelika Caputo, Amy Shah, Anke Post Affiliations expand

- A comprehensive review of the placebo effect: recent advances and current thought. Donald D Price, Damien G Finniss, Fabrizio Benedetti

- Affiliations expand placebo effects of a sham opioid solution: a randomized controlled study in patients with chronic low back pain. Regine Klinger, Ralph Kothe, Julia Schmitz, Sandra Kamping, Herta Flor

- Affiliations expand placebo effects of a sham opioid solution: a randomized controlled study in patients with chronic low back pain. Regine Klinger, Ralph Kothe, Julia Schmitz, Sandra Kamping, Herta Flor

- Placebos without Deception: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Ted J. Kaptchuk, Elizabeth Friedlander, John M. Kelley, M. Norma Sanchez, Efi Kokkotou, Joyce P. Singer, Magda Kowalczykowski, Franklin G. Miller, Irving Kirsch, and Anthony J. Lembo, Isabelle Boutron

- Fear-avoidance behavior and anticipation of pain in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled study. MPfingsten, E Leibing, W Harter, B Kröner-Herwig, D Hempel, U Kronshage, J Hildebrandt

- Conscious sedation with intravenous drugs: a study of amnesia SS Gelfman, R H Gracely, E J Driscoll, P R Wirdzek, J B Sweet, D P Butler

- Neurobiological and neurochemical mechanisms of placebo analgesia Livia Asan,corresponding author Ulrike Bingel, and Angelika Kunke. Pain 2022; 36(3): 205-212. Published online 2022 Mar 17. doi: 10.1007/s00482-022-00630-4 PMCID: PMC9156503 PMID: 35301592 Language: German | English